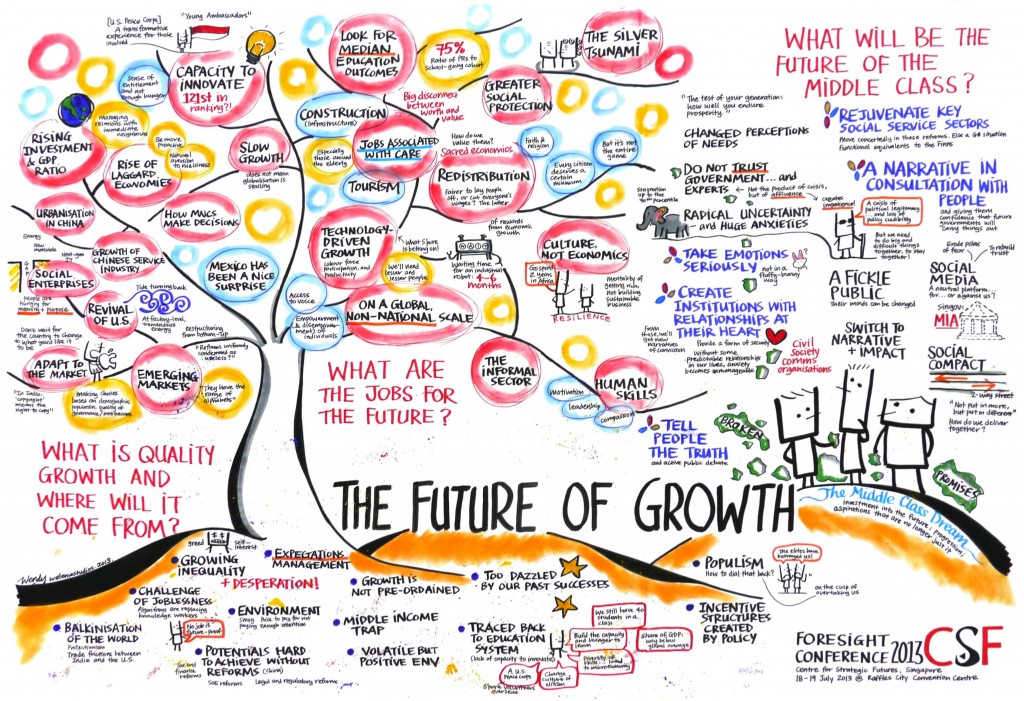

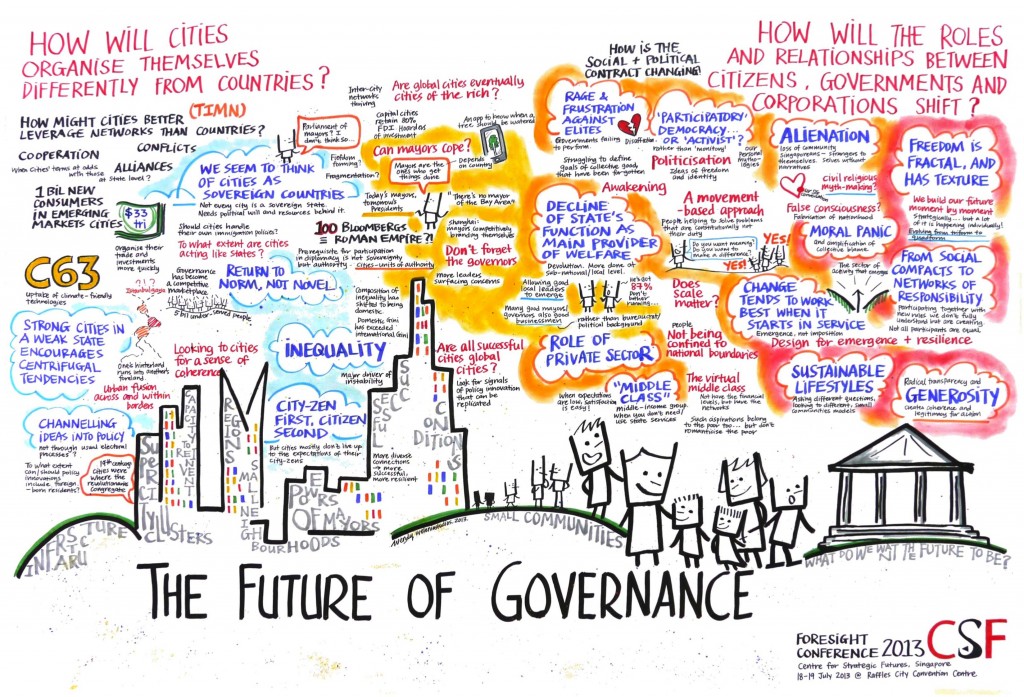

In 2011 the Prime Ministers office in Singapore sponsored a week of foresight conversations. This year saw the next iteration and I was invited back to the conversation. Once again there were about twenty of us from around the world that were invited, and the diversity of the conversation was only trumped by the quality. My notes are in mind-map form, and therefore I’m going to post some images from the event along with some insights and summation.

Firstly – the pictures:

Insights (in no order)

- It’s strategically important to have a good imagination and an adaptable mind.

- Most decision makers want simple answers, and ask the wrong questions. They want an answer, but in complex environments there may not be a simple answer.

- there is book called “Future Babble” that looked at previous predictions of the future, and found that the most inaccurate predictions were the ones that were most convinced of their accuracy.

- the real lack of skills in the world is the lack of generalists

- The waiting time to purchase a new industrial robot is 4-6 months.

- People are hard wired to take more notice of failure than success – from an evolutionary point of view it’s more important

- More insights are on my Twitter feed

Summary

To try to summarise the week is to fall into the trap of thinking conversation is a linear process. The discussions were so varied it’s almost impossible to bring it together, however the most important points for me related to foresight, policy and governance:

The world is becoming increasingly complex, and as a result leaders need to be adept at understanding that decision making can not always be causal. In order to make good decisions you need firstly to understand the environment you’re working in and Dave Snowden provides guidance here with his framework:

Dave Snowdens Cynefin (kin-are-fin) Framework

If you find yourself on the left hand side of the framework then you need to understand complexity theory, and acknowledge that there may be no right answer. That’s not easy for decision makers raised to believe that they need to make fast decisions based on minimal information.

I’ll close with a wonderful analogy that was provided in a conversation about the work of Karl Popper: you can begin to understand complexity through the lens of clouds vs clocks. You can take apart a clock to understand it, but to understand clouds you need to look at many different variables. Clouds cannot be taken apart.